From Shorts to Stardom: Busan’s New Currents Turns 30

Bong Joon Ho’s unique story-telling talents were first revealed to the world via the Busan International Film Festival’s New Currents award, some 12 years before the Korean filmmaker’s dark and dystopian drama Parasite picked up four Oscars and became a global box office sensation.

Jia Zhangke’s career was similarly still in its formative stages when his talents, too, were recognized by BIFF’s New Currents, a decade before the Chinese auteur was thrust into the global spotlight when his gripping rural drama Still Life won the Golden Lion at Venice in 2006

Busan’s New Currents has for 30 years showcased the early work of the region’s rising stars. In many cases it has also given them the attention — and the confidence — needed at a time when they are still trying to establish their industry credentials.

“Making a film with a low budget and winning the New Currents award is very inspiring, or very enabling,” says Malaysian filmmaker Tan Chui Mui, who won the New Currents with her debut Love Conquers All in 2006.

You Might Also Like

The 30th edition of BIFF sees the South Korean event charting new horizons as it transforms itself fully into a competitive festival, with main awards for best film, best director and best actors. But the New Currents mission hasn’t been lost amid all this change. The award remains a central festival focus and will now recognize “the most promising directorial debut” from Asia, with entries drawn from the “Competition” or “Vision” sections.

Bong was onboard as screenwriter — aged 27 and with only a few short films on his resume — when the Park Ki-yong-directed Motel Cactus became the first Korean winner of the New Currents at BIFF’s second edition in 1997. Motel Cactus producer Cha Seung-jae would then give Bong full control for his breakthrough cult hit Barking Dogs Never Bite (2000), while Park would later become hugely influential as chairperson of the Korean Film Council (KOFIC).

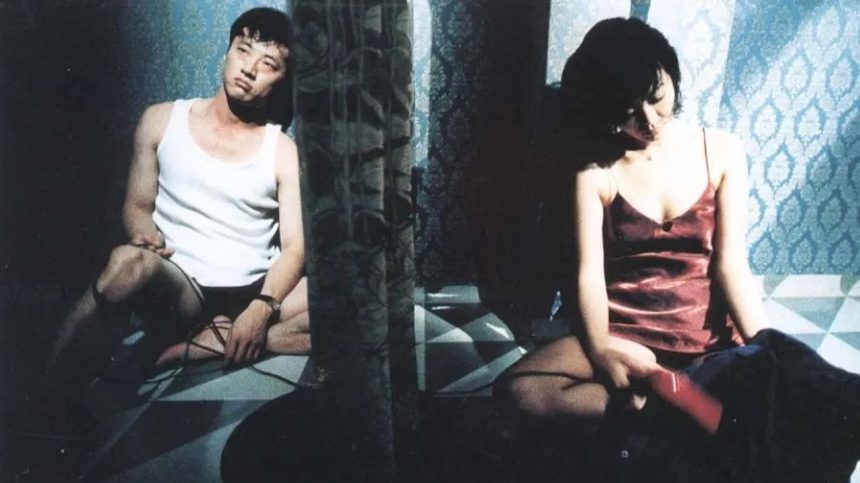

When Jia’s crime-soaked romance Xia Wu (or Pickpocket) won the New Currents in 1997, the Chinese filmmaker had made just two shorts and had only just graduated from the Beijing Film Academy.

Other now well-established Asian filmmakers to have their early work selected in the New Currents include Japan’s Palme d’Or-winner Hirokazu Kore-eda, Korea’s Im Sang-soo, Hong Kong’s Wai Ka-fai and Derek Tsang, China’s Wuershan, Singapore’s Eric Khoo and Iranian Jafar Panahi, also a Palme d’Or winner.

Mui’s victory in 1996 — and the $30,000 came with it — set in motion a career that has seen her become among the most influential filmmakers in Asia, capped by established the Da Huang pan-Asia production house and her Grand Jury Prize for Barbarian Invasion at the Shanghai International Film Festival in 2021.

Mui recalls learning she’d won via a surprise early-morning phone call, then rushing to a press conference “without the time to comb my hair.”

Later there was a swim in the ocean, and a moment looking back on Busan when Tan fully realized she’d “won the big prize!” before the closing night ceremony and the official award presentation, alongside co-winner Tang Heng, who won for Betelnut.

“There was something important happening that year, and I mentioned it during my speech,” she says. “I made my film with only 10,000 euro and Yang Heng made his film with only $3,000. I was hoping this would see [more] funding for low budget films in Asia, supporting first-time filmmakers like us.”

The late BIFF-programmer Kim Ji-Seok told Mui her plea helped him to push through what’s now known as the Asian Cinema Fund, while she used that $30,000 to support fellow Malaysian filmmaker Liew Seng Tat’s comedy Flower in the Pocket, which itself would go on to win the New Currents in 2007.

When Mui met director Midi Zhao in 2018, the Taiwanese Burmese filmmaker revealed he had attended BIFF as a student in 2006 and was inspired to make his own first film, The Man from Burma — which was selected for New Currents consideration in 2011.

New Currents has always cast a net wide across the region. Iqbal H. Chowdhury believes his win for the rural drama The Wrestler in 2023 was “the biggest achievement for Bangladesh’s cinema so far.”

“Our art cinema is gaining more worldwide recognition now than at any other time in our history, but until [that win] we had never won the top award at any A-list film festival,” he says.

Chowdhury says it has inspired a rising generation of Bangladeshi filmmakers as a whole, while it has also expanded his own horizons. “I recently met the great filmmaker Atom Egoyan in Toronto, and he told me, ‘Now you have to play at a different level’,” says Chowdhury. “So now I am trying to stay focused on my next feature.”