Gary Oldman on Almost Playing Edward Scissorhands, Bonding With Bowie and His “Diabolical Good Luck”

Gary Oldman is in a good place.

For an actor whose early career was defined by volatility — on- and offscreen — that’s no small feat. Born in 1958 in working-class New Cross, South London, Oldman came up through British theater before breaking out in the 1980s with fearless portrayals of damaged men: punk icon Sid Vicious in Sid and Nancy (1986) and murdered playwright Joe Orton in Prick Up Your Ears (1987).

By the mid-’90s, his talent for feral, unhinged roles — in Léon: The Professional, The Fifth Element, True Romance — had made him Hollywood’s go-to psycho. On Air Force One, Harrison Ford dubbed him “Scary Gary.”

But typecasting persisted. “I put myself out of work,” Oldman says of his decision to break free from his “rent-a-villain” persona.

You Might Also Like

The gamble worked. A late-career reinvention brought gravitas and restraint: Sirius Black in Harry Potter, police commissioner Jim Gordon in Christopher Nolan’s Dark Knight trilogy. These quieter turns reaffirmed his screen presence — without the pyrotechnics. (Getting off the booze helped. Oldman, now 28 years sober, says he used to “sweat vodka.”)

Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy (2011) earned him his first Oscar nomination, for a role so internalized it left him rattled. “It was a really naked role,” says producing partner Douglas Urbanski. “It almost gave him a nervous breakdown.”

“There was no hiding,” says Oldman. “I felt very exposed.”

More prestige roles followed. His towering performance as Churchill in Darkest Hour (2017) brought Oldman his long-overdue Oscar. Mank (2020), a more vulnerable portrayal of the witty, self-destructive Citizen Kane screenwriter Herman J. Mankiewicz, brought him his third nomination.

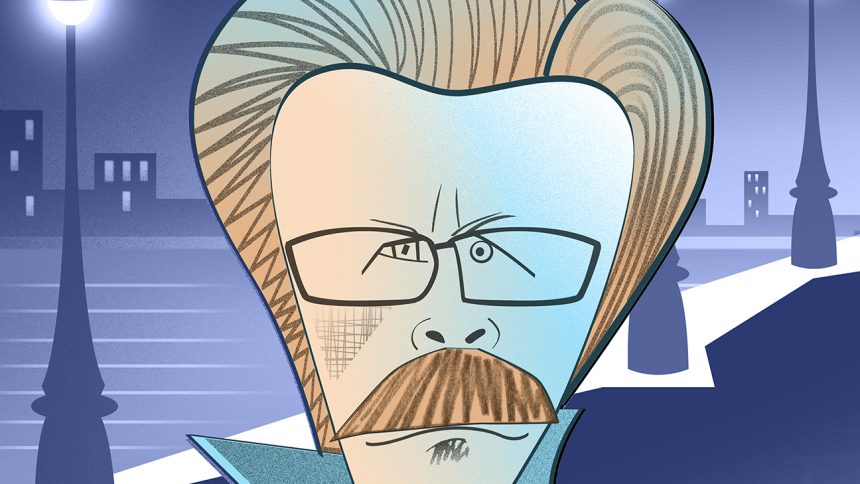

But his turn in Slow Horses — as the brilliant, disheveled MI5 misfit Jackson Lamb — may be his most complete yet. In the Apple TV+ hit, nominated for five Emmys, including best drama series and best actor for Oldman, he gets to fuse the feral, the funny and the fatherly (not to mention flatulent).

Now newly knighted (he received the honor from King Charles in June), Sir Gary Oldman spoke to The Hollywood Reporter about sobriety and second chances, convincing Nolan to cast him against type — and why playing the shambolic Jackson Lamb is one of the great joys of his career.

Let’s start like a therapy session. Tell me about your childhood: How did the way you grew up influence your work?

Well, the work itself comes from the life experience. I’m not playing the piano or a violin. The instrument is me. You draw on your life experience. I come from a working-class family. I wouldn’t say that we were on the bread line, but we didn’t have a great deal of money. I was very well looked after as a kid. My mother brought me up. My mother held down three jobs at one time to support us.

It sounds cliché, but the arts — acting — was a way of escaping from the options that were available. Not that it was all so horrendous, but discovering acting was a sort of window that opened onto the world.

My mother was behind the dream, the ambition. I didn’t have any resistance. I wasn’t from a family where they wanted me to be a doctor or a lawyer. This profession is precarious, and at any one given point, you know, 99.9 percent of the profession are out of work. So there was no security in wanting to go into the arts. I’ve a work ethic, and some talent, but really I’ve just had diabolical good luck. I’ve had the usual sort of peaks and valleys of any kind of career. But for the most part, I’ve worked consistently as an actor, and that is extraordinary.

What was the turning point, the breakout moment in your career?

I started to make a name for myself on the stage early on, in the theater, and I was quite happy doing that. It wasn’t as if I had some big burning ambition to be in film or television. Then I did Sid and Nancy, and I went back to the theater. Back then, I’d do a film and then a play. Theater was my main thing, cinema sort of an interesting sideline, an opportunity to work in another medium, and certainly make more money than you could in the theater. I remember I did Sid and Nancy, then Women Beware Women at the Royal Court. Then I did Prick Up Your Ears.

In Sid and Nancy, I was playing a down-and-out, heroin-addicted punk rocker. And then in Prick Up Your Ears, I was playing a homosexual British playwright. And so the contrast showed, quote-unquote “versatility.” But that wasn’t engineered — it was just luck. Having those two roles back-to-back sort of put me on the map.

You had a huge run playing baddies in Dracula, The Professional, The Fifth Element, Air Force One. Was it a conscious choice to move away from that?

There was certainly a time where I felt that I was being sort of typecast. I was a sort of “rent-a-villain,” you know what I mean? But when you get known for those kinds of roles, it’s a hard ship to turn around. I made a conscious decision that I can’t do this anymore. I put myself out of work to wait for something to come along that was as far away from the sort of villainous world I was in.

I was lucky to be able to do the franchise bit — to be part of the Harry Potter series, and then the Batman series. That pedigree, that profile, allows you to do things like Tinker Tailor. One feeds the other, right?

How did you get cast as James Gordon for Batman Begins? It’s pretty much your first purely good character.

If I remember correctly, they approached me to play a villain, it may have been Scarecrow. And I said, “No, I don’t want to play another weirdo.” It may have been Doug [Urbanski] who said: “What about Jim Gordon?” To his credit, Nolan thought about it, found it interesting.

It’s like we’ve been talking about good fortune. I was in the running for the role of Scarecrow, and after Chris met me he found the idea of me playing Jim Gordon very intriguing. Cillian Murphy got the Scarecrow role, which is the first time Chris worked with Cillian. So if that hadn’t happened, would he have gone on to play Oppenheimer?

I’ve heard so many sliding-door moments with you. Weren’t you considered to play the lead in Edward Scissorhands?

Well, that’s going back a few years. It would have been in the late ’80s. I was on Tim Burton’s list for the role of Edward Scissorhands. It was a small list. My agent thought I had a really good chance of getting it. They said to me, “Read the script.” They sent the script over, and I basically said, “I don’t get it.”

You have to remember at this point in time you’re not looking at Tim Burton’s whole body of work. I read this quirky, strange little script, and I didn’t get it. The Avon lady and the kid with the scissor hands. It just didn’t register with me. I said to the agent, “I just don’t understand this. It’s not my cup of tea.”

So I did not meet Tim Burton. Then Scissorhands came out and I went to the cinema to watch it. With that opening shot — all those brightly colored houses, and then the camera pans up to the castle-like thing on the hill — within two minutes I went, “I get it!”

What was the most challenging role for you to crack?

I come at the roles with different things. Everybody has some kind of motor. It might run more slowly than others, or it might be more frenetic, but I try to find that physicality. Music is often a key. When I did True Romance [playing dreadlocked pimp Drexl Spivey], I listened to a lot of rap music to find the energy of the character.

A tough one to crack — the one that gave me the most anxiety — was George Smiley [in Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy], because it’s all internal. His wonderful mind is the motor running inside, but externally, it’s all still. Plus the fact that I was in the shadow of Alec Guinness, who had incredible success with the role — Sir Alec Guinness, this great, revered and loved British actor. It was a bit cheeky of me to come along and say, “OK, you thought he was good — get a load of me.” They were big shoes to fill. I found it overwhelming.

Did you feel more exposed in the role, without a crazy wig, prosthetics or an accent to hide behind?

Yeah, there was no hiding. I felt very exposed. I felt this was the one where they’re going to tap me on the shoulder and go, “You’re a phony.”

You’ve spoken publicly about your struggles with addiction. Has going through recovery influenced your work?

It’s had an influence on everything. I wouldn’t be sitting here talking to you. I’m in a very good place at the moment, and a lot of that is to do with sobriety. It’s been 28 years. There was a point when I didn’t think I could’ve gone 28 seconds without a drink.

My heroes — literary heroes, film heroes, theater heroes, athletic heroes, musical heroes — they were all sorts of drunks and drug addicts. They were all tortured poets and artists. You look up to them and you romanticize and want to emulate them.

But I didn’t start drinking because I liked Hemingway. It was a social norm, and at some point it got out of control. And that’s nothing to do with anyone other than me. But you do glamorize it. That sort of crazy behavior. You read about Richard Burton, who I think did 136 performances of Hamlet, eight shows a week on Broadway. He’d drink a whole bottle of vodka and then play the whole part completely drunk.

You hear these sorts of stories, and you glamorize them, and you think it’s giving you an edge — and it’s not. It’s just an excuse, really, and you’re just kidding yourself.

My own life, my personal life, is immeasurably better from just not living in a fog. But I think the work is good, too. Going at the rate I was going, I wouldn’t be sitting here with you by now. I’d either be dead or institutionalized.

It’s been 10 years since the death of David Bowie, who was a good friend of yours. What did you learn from him?

To push the boat out. David always said, “When you’re wading out into the water and you can feel the sand beneath your feet, you feel safe and calm. But if you just go a little bit farther where your feet don’t quite touch the bottom, you’ll be in a place where you can do your best work.”

We laughed a lot — a lot. He was very, very, very funny, David. And we sort of had similar kinds of backgrounds, grew up in similar neighborhoods. So we had that connection.

But he was always pushing the envelope. He reinvented himself and his music many times. He was inspiring because he was a great innovator and not afraid to try things. It’s nothing conscious, but that rubs off.

And Dave … well, don’t you feel that since he died, the world’s gone to shit? It was like he was cosmic glue or something. When he died, everything fell apart. So, yeah, I miss him. Occasionally, I’ll see something, it’ll make me laugh, and I’ll think, “God, I wonder what Dave would have made of this,” or “Oh, that would have made him laugh.”

Your role as Jackson Lamb in Slow Horses shows off your comedic side, something we haven’t seen as much of in your career.

Well, I’ve been known to be, occasionally, funny. People over the years have always said, “Why don’t you do a comedy?” But you’ve always got to show them. People are very skeptical in this business; until you show them, they don’t know. So I never got comedy. I was never up for a comedy.

Jackson Lamb is glorious to play because of that insulting humor. He basically gives the finger to the establishment. I think what makes him work are all those things, the raincoat, greasy hair, that go against the way things are supposed to be. He smokes because we’re not allowed to now. Otherwise, he would probably give it up. And it’s part of his spy craft. People underestimate him, and that plays to his advantage. Plus, he just doesn’t give a shit.

He might not have social graces, he might not be politically correct, but there’s a loyalty there. His team of slow horses is like a dysfunctional family. As rude and obnoxious as he is to them, he would defend them to the death. There’s a moral compass there, and that’s what people respond to.

Slow Horses is your first major television role. How are you enjoying the rhythm of making serial TV?

I love it. I like returning to a familiar character. Lamb is not going to suddenly announce that he’s going to be a physicist, or that he’s got a wife somewhere and four kids. There’s no jumping the shark, no big character development coming. The die is set. He’s a cousin of Smiley in a way — in that he’s often playing chess when everyone else is playing checkers.

And I love the writing. The world that [Slow Horses creator] Mick Herron has created is fantastic. It’s in the spy genre, but it’s not James Bond, all casinos and martinis and tuxedos. It’s more the world of [Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy author John] le Carré. But le Carré can be quite dry. What Mick has done is given you the le Carré world and then shaken it up and put in an enormous amount of humor.

So it’s nice to step back into this world and see the crew and those actors again and again. I miss them. When we’re packing up to go to London to start another season, my wife and I often say, “I can’t wait to see Kris [Kristin Scott Thomas] again, I can’t wait to see Jack [Lowden]. And Vince [McGahon] the camera operator, and Josh [Close] the grip and Lucy Sibbick, Dominique [Wallaker] and Demi [Amat], who do the makeup.

It’s like a family. It’s really lovely, and I’ve never experienced it. There was a little of that with Potter and Batman. But I wasn’t in a team. James Gordon doesn’t have a sidekick. I love the Slow Horses family. It’s been a real highlight in my career.

This story appeared in the Aug. 13 issue of The Hollywood Reporter magazine. Click here to subscribe.