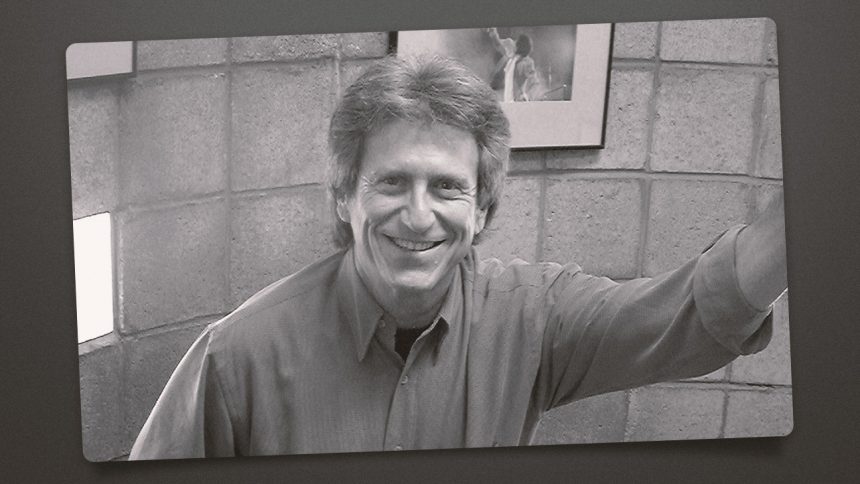

Michael Ochs, Pop Culture’s Preeminent Photo Archivist, Dies at 82

Michael Ochs, the obsessive collector whose one-man crusade to preserve moments of music and entertainment pop culture made him the preeminent photo archivist of his and perhaps any era, has died. He was 82.

Ochs died Wednesday at his Venice Beach home in Los Angeles, his wife, Sandee, told The Hollywood Reporter. He had been diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease five years ago and was dealing with COPD, kidney and heart issues as well, she said.

In February 2007, he sold his Michael Ochs Archives for an undisclosed amount to Getty Images. At the time, it included some 3 million vintage prints, proof sheets and negatives of musicians and film, TV and political personalities from the 1940s to the 1990s. Many photos hadn’t been seen in decades; some had never been seen.

His 1984 book, Rock Archives: A Photographic Journey Through the First Two Decades of Rock & Roll, put him and his collection on the map, and his materials were licensed for album and CD reissues — think those from Rhino Records in particular — books, magazines, news sites, features and documentaries.

You Might Also Like

In 1987, Ochs, the younger brother of folk singer Phil Ochs, discovered several rolls of negatives of Marilyn Monroe shot by Ed Feingersh for Redbook magazine in March 1955. A year later, he paid about $50,000 for the collection of James Kriegsmann, who had photographed Frank Sinatra, Kate Smith, Buddy Holly and hundreds of other stars.

Along the way, Ochs also acquired more than 100,000 negatives shot by beatnik photographer Earl Leaf, the house man for The Beach Boys, as well as other collections from photographers Don Paulsen and Richard Creamer and magazines including Hit Parader, Tiger Beat and Rona Barrett’s Hollywood.

THR featured a handful of photos from his archive in an April 2024 issue.

“As I always say, had I planned this, I would’ve failed,” he told TheAustin Chronicle in 2009. “It was right place, right time. It was the kind of thing that needed to be done, and luckily, I had the luck and the skill to do it.”

The youngest of three kids, Michael Andrew Ochs was born on Feb. 27, 1943, in Austin, Texas (he only spent six months there). His parents, New York native Jack and Scottish-born Gertrude, met and married in Edinburgh, where Jack was attending medical school.

His dad wound up working at a series of hospitals around the country, and Ochs was mostly raised in Far Rockaway in Queens; Perrysburg, New York; and Columbus, Ohio, attending three high schools in four years while stockpiling albums.

“I’d go to school, didn’t know anybody. I’d come home and play records,” he told the Los Angeles Times in 1992.

After following Phil to Ohio State University and graduating in 1966 with a bachelor’s degree in radio and TV writing, he served as his brother’s manager and came to Los Angeles, where he worked as a photographer and PR exec at Columbia Records.

“They didn’t pay you much, but [you got] all the records you could eat,” he told TheBoston Phoenix in 1984. “Every week I’d go through a different letter in the catalog. The first year I had 3,000 albums, the second year about 10,000.

“I saw them start to throw away photos of performers who were dropped from the label and went, ‘Wait a minute, I’ll bet the photos will became just as rare [as the records], too.’ I only began collecting them because I was such a music junkie that I wanted to document everything.”

When people like Lester Bangs and Dave Marsh at Creem magazine needed photos for retrospective stories, he supplied them, for free. But when the Los Angeles Free Press credited one of his shots to the “Michael Ochs Archives,” he thought, “That’s a good way to justify this obsession — let’s call it an archive.”

He knew he was onto something when he got a surprise check for $1,000 for photos he had turned over for one of Dick Clark’s Rock and Roll Years specials at ABC in the early 1970s. “I gave him the stuff for nothing, expected nothing,” he said. “I thought, hmm — this could be a business here. Then I began to take it real seriously and started fanatically trying to find as many photos as I could.”

“Scooping up material from estates, photographers, ex-writers, defunct publishers, other collectors, the artists themselves and the garages of retired record company employees, Ochs has generated an irresistible mass and momentum for his enterprise,” the L.A. Times wrote. “The bigger it gets, the easier it is to get more.”

Rolling Stone used some of Ochs’ pictures in a 1976 book, Illustrated History or Rock & Roll, with a photo of obscure rockabilly singer Ersel Hickey leading things off. He really broke through with Rock Archives in 1984.

“Without fanfare, Mr. Ochs presents the ruffliest bell-bottoms, the spikiest stilettos, the wildest pompadours and the strangest likenesses of singers who’ve been seen much more rarely than heard,” Janet Maslin wrote for The New York Times.

“Mr. Ochs’ book is invaluable for its particular attention to lesser-known Black performers and for its rare, conversation-piece photos of Joan Rivers as part of a folk-comedy trio, Sissy Spacek as a flower-child singer called Rainbo and the barely adolescent Paul Simon as part of Tico and the Triumphs. It’s also the book for anyone who wonders, say, what Question Mark and the Mysterians looked like. They looked much, much stranger than their name.”

Later, he hosted an Archives Alive radio show on KCRW in Los Angeles and taught a class about rock ’n’ roll history at UCLA Extension.

Ochs contributed to several Andrew Solt documentaries, including Heroes of Rock and Roll (1979), This Is Elvis (1981) and Imagine: John Lennon (1998), and was a music coordinator on such films as Liar’s Moon (1981), Losin’ It (1983) and Christine (1983).

He also was a producer on the 2010 documentary Phil Ochs: There But for Fortune. (His brother died by suicide in 1976.)

Ochs housed much of his collection in a temperature-controlled concrete fortress he built on his property. He had given away or sold most of his records.

In addition to his wife, whom he married in Maui in September 2002, survivors include his sister, Sonny; his nephews, Johnny and David; and his niece, Meegan.

In the L.A. Times piece, Ochs explained how he acquired some of his material. “I use this concept, which could come off as B.S., but I use it to talk people out of stuff,” he said. “It’s the greater good concept: ‘It should be in the archives, and you know it.’”

Ash Barhamand contributed to this report.