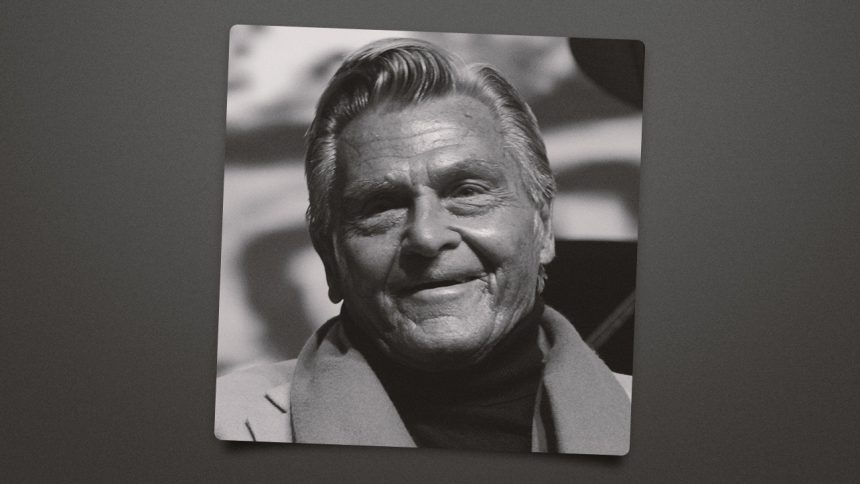

Vince Calandra, ‘Ed Sullivan Show’ Talent Booker Who Helped Bring on The Beatles, Dies at 91

Vince Calandra, the charismatic Ed Sullivan Show talent booker who graduated from gofer and cue-card guy to bringing such talent as The Beatles, Julie Andrews, Alan King and Jackie Mason to the legendary CBS variety hour, has died. He was 91.

Calandra died Saturday of natural causes at his home in Woodland Hills, his daughter, Christine Calandra Farrell, told The Hollywood Reporter.

Survivors also include his son, Vince Calandra Jr., a writer and/or producer on The Ren & Stimpy Show, Sharp Objects, Dark Winds and many other shows.

A street-smart Brooklyn native, Calandra Sr. started out in the mailroom at the Sullivan show in 1957 — nine years into the Sunday night program’s run — and stuck around through its final episode on March 28, 1971. The show was recorded live.

In a 2003 chat with Jeff Abraham for the Television Academy Foundation website The Interviews, Calandra said he always followed Ed Sullivan’s philosophy as a talent booker: “Open big, keep it clean and put something in there for the kids.”

The afternoon before The Beatles’ historic first performance on the Sullivan show on Feb. 9, 1964, Calandra stood in for George Harrison — even wearing a wig — at the dress rehearsal when the guitarist was back at the hotel with bronchitis.

He also was the person who had to tell The Doors and The Rolling Stones to change lyrics in their songs “Light My Fire” and “Let’s Spend the Night Together,” respectively. Lead producer Robert Precht did not want Jim Morrison using the word “higher” — as in “Girl, we couldn’t get much higher” — and preferred that Mick Jagger sing “Let’s spend some time together.”

The Doors “said they would [comply], but they never intended to do it,” Calandra told Forbes in 2020. “They did the show and Bob Precht was furious, Ed was furious, and program practices was like all over us afterward.” The group never appeared on the show again.

Jagger, meanwhile, “was not too happy when I told him that. He really wasn’t. But he did change the lyric.”

Vincent Leonard Calandra was born on April 22, 1934, in Jersey City, New Jersey. His mother, Anna, died in childbirth, and he was raised by Italian-speaking grandparents, Vincenzo and Rose, in Brooklyn. His father, Leonard, worked for the Brooklyn Union Gas Co.

An excellent high school baseball player, Calandra received scholarship offers to several colleges and was drafted by the New York Giants. The team sent him to spring training in Florida, where he wound up serving as Richard Jaeckel’s stand-in in the 1953 movie Big Leaguer, starring Edward G. Robinson.

Calandra joined the U.S. Army when he was 18 — he would guard an early atomic bomb in Texas — and after two years in the service was taking classes at St. John’s University when he landed a job in the Sullivan mailroom in 1957.

“I went down to the theater and met Mr. Sullivan. He took an instant liking to me,” he said. “I was a street guy, brought up in New York. Never [graduated] college. He felt a bond with me. I knew all the movies and was a sports fanatic, so I could talk to him.”

Soon, Calandra was promoted to delivering telegrams, then worked as a gofer and then as the cue-card guy. He wrote out the cards and held them up during the show, mostly for the benefit of the host and the stand-up comics.

“Sullivan rehearsed over and over and over again,” he said. “You had to be really with him. You turn your head this way and he’d jab you and say, ‘Goddamn it, look at me, don’t ever do that again.’ … It was always intense. You just couldn’t make mistakes.”

After a stint in the CBS film department, Precht — Sullivan’s son-in-law had been promoted to producer in 1960 — put Calandra back in charge of cue cards, and he made a living on the side doing similar duty for the likes of King, Garry Moore and Vic Damone.

He worked as a program coordinator for Sullivan before succeeding Jack Babb as the show’s talent booker in 1963, getting a raise to $300 a week, plus $100 week for expenses. He would scout Broadway shows and nightclubs acts, people like George Carlin.

For The Beatles’ first Sullivan show — which drew a then-record 73 million TV viewers — Calandra said he fielded 50,000 requests for tickets for a theater that seated 720 people (among the celebrities that wrangled their way in was Leonard Bernstein). He described himself as “the go-to guy in New York and Miami” when the Beatles performed. He also helped produce their concert at Shea Stadium in 1966.

He said booking Andrews and Richard Burton for a 1966 performance of “What Do the Simple Folk Do?” from Camelot was among his Sullivan highlights.

Calandra also was there in 1964 when Mason might have given gave Sullivan the finger after his routine was cut short. (When the comic was banned for that and not paid, he sued, and Calandra represented the show in court, where he said the judge had seen Mason in the Catskills and was a big fan. Mason ended up getting paid and returning to the program.)

After the Sullivan show was canceled, Calandra worked with Billy Joel at a record company and booked celebrities for talk shows hosted by Mike Douglas, John Davidson, Alan Thicke, Dinah Shore, Vicki Lawrence and Joan Rivers; for the syndicated programs Solid Gold and Entertainment Tonight; and for many star-studded 100 Years … TV specials for the AFI.

Some of the “gets” he was most proud of: James Cagney, Jack Nicholson, Frank Sinatra, Jimmy Stewart, Marlon Brando, Laurence Olivier, Fred Astaire and Meryl Streep. His Rolodex was the envy of many in Hollywood.

In addition to his daughter and son, survivors include his grandsons, Enzo and Liam; his daughter-in-law, Marjorie; and his son-in-law, Michael. His wife, Marge, whom he married in June 1960, died more than a decade ago.

On the Sullivan show, he told Forbes, “We produced the people that were on, and we had sets for them. We rehearsed them on a Saturday, blocked them on camera and took the time to do it on Sunday at a dress rehearsal. We wanted to make sure the audio was right and they were happy.

“Then of course the record companies loved us because we sold records. Even the guys that had one-hit records years later — I ran into them at shows, these reunion shows — I would hear comments from [them] that their one record wound up paying for their kids’ college. It’s amazing how many lives you touch by doing that show.”