The 10 Best Medical Shows of All Time, Ranked

As I wrote in my review of Max’s The Pitt, it feels as if the collective bingeing of shows like ER and House during the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic has finally paid off in a resurgence of the medical genre on television.

It wasn’t like we were formerly living in a medical desert. Shows like New Amsterdam and The Resident recently completed solid and selectively beloved runs, while Grey’s Anatomy will outlive us all. But the recent explosion has felt notable, with January releases like The Pitt, Fox’s Doc and CBS’ Watson joining fall offerings like NBC’s Brilliant Minds and St. Denis Medical, plus ABC’s Doctor Odyssey.

What a perfect opportunity, then, for everybody’s favorite thing: listing!

As with all good lists — see our assembly of the 50 Best TV Shows of the 21st Century So Far — this ranking of the 10 Best Medical Shows of All Time is a living thing, one that may not have been identical a month ago and may not be the same in a year.

You Might Also Like

A couple of disclaimers.

Disclaimer 1: Because I rewatched a lot of medical shows to put this list together, a bunch of classic series that aren’t available to stream were left off. Nobody is questioning the importance of shows like Ben Casey, Dr. Kildare and Marcus Welby, M.D. to the genre, but studios are inexplicably keeping those chapters of our cultural history under lock and key, like Kleenex at CVS. It isn’t just vintage classics, mind you. CBS’ City of Angels, which ended its two-season run back in 2000, feels like an important show in retrospect, but it isn’t streaming anywhere, so I couldn’t revisit it.

Disclaimer 2: Could shrinks count for the purposes of a list like this? Probably! Do shrinks count for the purposes of this list? No. Gotta draw the line somewhere. Thus, sorry In Treatment and Shrinking and The Patient and The Bob Newhart Show and Dr. Katz, Professional Therapist and The Sopranos and Hannibal and Frasier and Sex Education. See? It’s an entirely different list.

So, let’s get down to business.

During its three-season run, I don’t think audiences fully appreciated the core quartet of stars at the center of Getting On. In Laurie Metcalf, Alex Borstein, Niecy Nash and Mel Rodriguez, creators Mark V. Olsen and Will Scheffer had performers capable of taking a setting that frequently ran the risk of suffocating darkness — the geriatric rehabilitation ward at a struggling Long Beach hospital — and delivering humor that ranged from bleakly cynical to broadly physical. Airing only 18 episodes, Getting On is one of the best shows ever made about aging, caregiving and death, three topics Hollywood productions typically avoid like … well … one of the maladies troubling the patients in the Billy Barnes Extended Care Unit at Mount Palms Memorial Hospital.

Underestimate Grey’s at your peril. Shonda Rhimes’ Seattle-based drama, which aired its 438th episode last fall … actually. Wait. Let’s pause there. Four hundred and thirty-eight episodes? That’s almost a full Private Practice — the Grey’s Anatomy spinoff that aired 111 episodes — more than ER. Not bad for a show that has too often been overlooked or mocked because of its proud soapiness, frequently twee soundtrack, silly Mc-nicknames, that one time Izzie had sex with a ghost, various other (entirely unfair) things related to Katherine Heigl, and the scandal related to writer Elisabeth Finch. With Grey’s Anatomy, that’s only the smallest part of the story, of course, because the ABC drama has proven time and time again that it has the heart to generate one passionate in-show relationship after another; the guts to tantalize viewers with bombs and plane crashes and shootings and ferry disasters; the brains to tackle COVID as directly and as well as any show on TV; and the resilience to populate cast after cast with new stars whenever necessary.

Never perceived as a stand-alone smash during its two-network run, Scrubs was recently announced for a series reboot, reflecting how thoroughly audiences have caught up with the show’s sensibility over the past 15 years. The workplace bromance between Zach Braff’s J.D. and Donald Faison’s Turk has become so adored that Braff and Faison’s chemistry is still being used in commercials that don’t even acknowledge the relationship’s origins. John C. McGinley’s Dr. Cox has become foundational for so many tough-but-affectionate comic authority figures that if you told kids today that McGinley was never nominated for a single Emmy for the show, they’d say … “What’s an Emmy?” And series creator Bill Lawrence’s gift for hangout comedies infused with heart — and with tears right around the corner — has only become more refined as it evolved from Cougar Town into Ted Lasso and Shrinking.

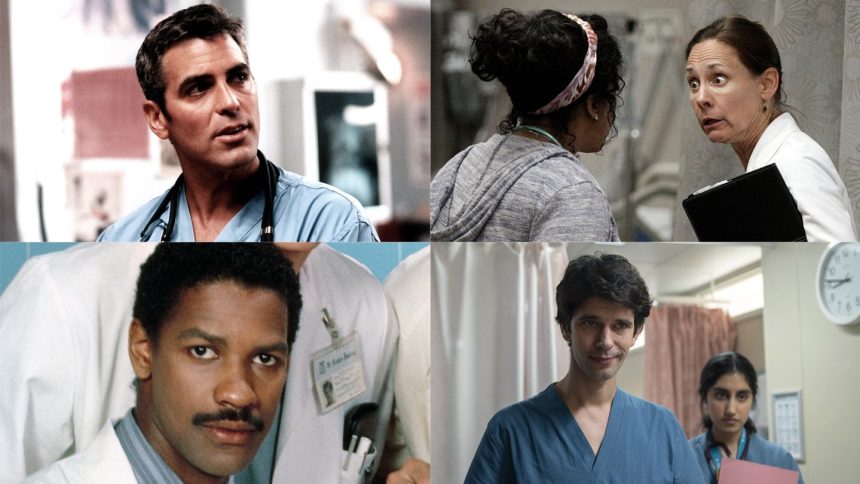

A pragmatic and unflinching look at life in the obstetrics and gynecology ward in a London National Health Service hospital, This Is Going to Hurt has been the best and most clear-eyed medical drama of the post-pandemic era thus far. The semi-autobiographical black comedy from Adam Kay features Ben Whishaw at his peak as a brilliant young doctor you probably wouldn’t want to find yourself visiting and a breakout performance from Ambika Mod as an inexperienced doctor … whom you also probably wouldn’t want to visit. Really, with the possible exception of The Knick and The Kingdom, no show on this list features a medical environment as unappealing as the one in This Is Going to Hurt, which is part of the point: Even the best doctors in a system we think is, in many ways, enviable can fall victim to circumstance, bureaucracy and fate. It’s scary and funny and gross and brilliantly written and performed.

Don’t dwell on the later years, with the menacing season-long adversaries or the confusing revolving door of underlings. No, concentrate on Paul Attanasio and David Shore’s venerable series in its purest form: those early seasons, when Hugh Laurie’s Gregory House and Robert Sean Leonard’s James Wilson played Holmes and Watson to the most diabolical medical mysteries imaginable via perfectly crafted 43-minute puzzles in which the only sure thing was that it was never lupus. House isn’t the best medical drama in TV history, but it’s very possible that Laurie’s performance is a genre pinnacle — a limping, quipping, socially uncomfortable bundle of genius, misanthropy and stealthy empathy who pinballed perfectly around the rest of an ensemble initially featuring Lisa Edelstein, Jesse Spencer, Jennifer Morrison and Omar Epps, all in fine form and all bringing out different shadings from the series’ caustic centerpiece.

Long before audiences came to blows over whether The Bear is actually a comedy, Larry Gelbart’s series adaptation of Robert Altman’s acclaimed film should have proven just how arbitrary comedy/drama lines can be. There were 256 episodes of M*A*S*H, and depending on the week, the series could use its Korean War setting to be a scathing critique of the Vietnam War, a wacky workplace sitcom, a harrowing medical drama or a sentimental reflection on life’s fragility — all evoked instantly any time fans hear the tune of Johnny Mandel’s “Suicide Is Painless.” The series delivered a timeless finale, possibly TV’s most shocking deaths (or at least its most shocking deaths not involving an elevator shaft or a wayward bus) and more indelible characters than I can count, held together by leading man Alan Alda, who also wrote and directed dozens of episodes.

Twenty hours dedicated to the noncontroversial proposition that we should all be thoroughly relieved that we aren’t seeking medical help at the turn of the 20th century, The Knick helped Cinemax establish itself as a home for quality drama. And then Cinemax stopped making original shows. Oh, well. Jack Amiel and Michael Begler’s drama, a fantasia of surgical misadventures, opium dreams and a New York City on the cusp of a modern revolution was an exceptional showcase for stars Clive Owen and André Holland, an introduction to future stars like Eve Hewson and Chris Sullivan and an absolute playground for Steven Soderbergh. Working with “frequent collaborators” Peter Andrews and Mary Ann Bernard, as well as composer Cliff Martinez (who to the best of my knowledge is not actually Steven Soderbergh in disguise), Soderbergh made a show that looked and moved and sounded like no medical drama before or after.

Had this Joshua Brand- and John Falsey-created series just continued with its initial mission of being “Hill Street Blues in a hospital,” that would have been enough to write the entire genre. The early episodes are gritty, chaotic and set a template for nearly every medical series to follow. As the show progressed and shifted its creative mandate, St. Elsewhere became freer, more self-reflexive, more willing to play to extremes in humor, cliffhanging drama and emotion, jumping around in time or the afterlife — or just enjoying the artificiality of being a television show at a pivotal moment for the medium. St. Elsewhere gets points for the countless influential writers who shaped its narrative and the constantly shifting and evolving ensemble of actors who made their way through the halls of St. Eligius. It loses points for having Denzel Washington as a cast regular for six seasons without ever recognizing or utilizing the skills that would eventually make him Denzel Freaking Washington.

A blending of St. Elsewhere and Twin Peaks — which is to say “St. Elsewhere, but dialed to 11″ — Lars von Trier and Tómas Gislason’s Danish-Swedish series is delightful because one moment it’s a totally run-of-the-mill medical series with doctors experimenting with new procedures, struggling with a lack of resources and trying to get laid; the next minute you remember the hospital was built on an ancient Indian burial ground (“the bleaching ponds,” if you want to be technical) and there’s a ghost ambulance, a freaky little girl hiding in the elevators, spectral impregnation and a Greek chorus of dish-washing orderlies with Down syndrome (an aspect of the show that probably could have aged better). The Kingdom — or Riget in its native land — is a jittery, unsettling nightmare of a show, except for when it’s weirdly and inexplicably hilarious. Awash in von Trier-ian weirdness, the series is particularly notable for Eric Kress’ cinematography, which makes every image look like it was dragged through the Stygian depths, some of the most gorgeously ugly images ever captured.

Led by early directors Rod Holcomb and Mimi Leder, and writers overseen by Michael Crichton and John Wells, ER perfected the formula that St. Elsewhere aspired to in its earliest days: blending multiple patient-of-the-week cases, the high stakes of a thriller and bigger-picture conversations about medical ethics into a single, breathlessly paced, Chicago-set tapestry. Watch St. Elsewhere and then any previous medical drama, and the latter feels slow. Watch ER and then St. Elsewhere, and the latter feels slow. Part of the reason viewers were willing to hop on this jargon-filled freight train was a cast that functioned like a snake, sloughing off layer after layer of stars but retaining its basic shape and its unfailing ability to shock long after the repetition of drug overdoses, violent emergency room infiltrators and nefarious helicopters should have begun to fatigue.